Self-hosted Security

NAT

Traversal, VPNs, and Solutions for Remote Access to

Resources*

February 2, 2026

1. Introduction

Despite the massive growth and consolidation of Cloud platforms over the past decade, there remains a steady interest in the Cloud’s antithesis: self-hosting. An extension of the broader category of DIY infrastructure — which includes volunteer Mesh networks, community radio stations, and cooperative gardens — self-hosting is the practice of building, maintaining, and securing one’s own services and applications.1 Though self-hosting affords digital agency in a landscape fraught with personal data mining and opaque privacy policies, it comes with a crucial tradeoff. Administering self-hosted servers requires time, resources, and perhaps most importantly, a working knowledge of security and networking. Throughout the configuration process, the administrator makes choices between security and convenience, while assessing threat models against home or community networks.

This work attempts to make the consequences of these choices clear with an in-depth analysis of the attack surface against home media servers. We begin with an overview of the default security mechanisms implemented in most home routers, specifically Network Address Translation (NAT). We explain the importance of NAT in securing home networks, but also how it complicates remote access to self-hosted resources. Next, we discuss two solutions to NAT traversal: Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) and manual port forwarding. We argue both approaches do not guarantee sufficient protection against attacks. With these considerations in mind, we survey vulnerabilities of two popular applications for media servers, Plex and Jellyfin, highlighting the risks of exposing these services directly to the Internet. Finally, we present two improvements on NAT traversal: port forwarding services (PFS) and virtual private networks (VPNs). Though PFS offer a slight improvement over UPnP, we explain their weaknesses through a recent research report. We argue VPNs offer a solid layer of protection for self-hosted services on home networks, but come with significant technical overhead. We conclude with suggestions on how to simplify the configuration of VPNs on home networks through the use of third-party Mesh VPNs like Tailscale.

2. Background: Network Address Translation and Firewalls

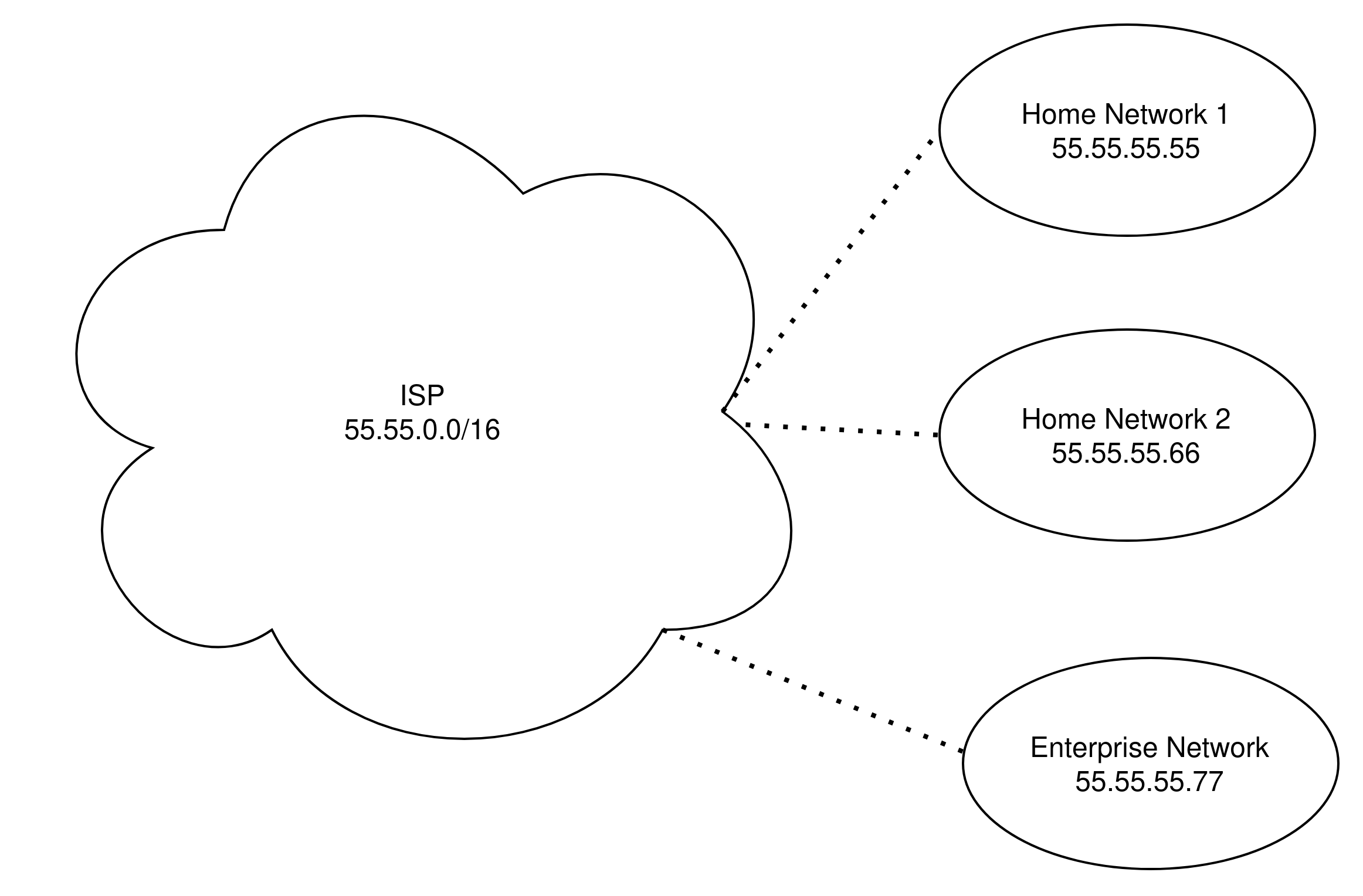

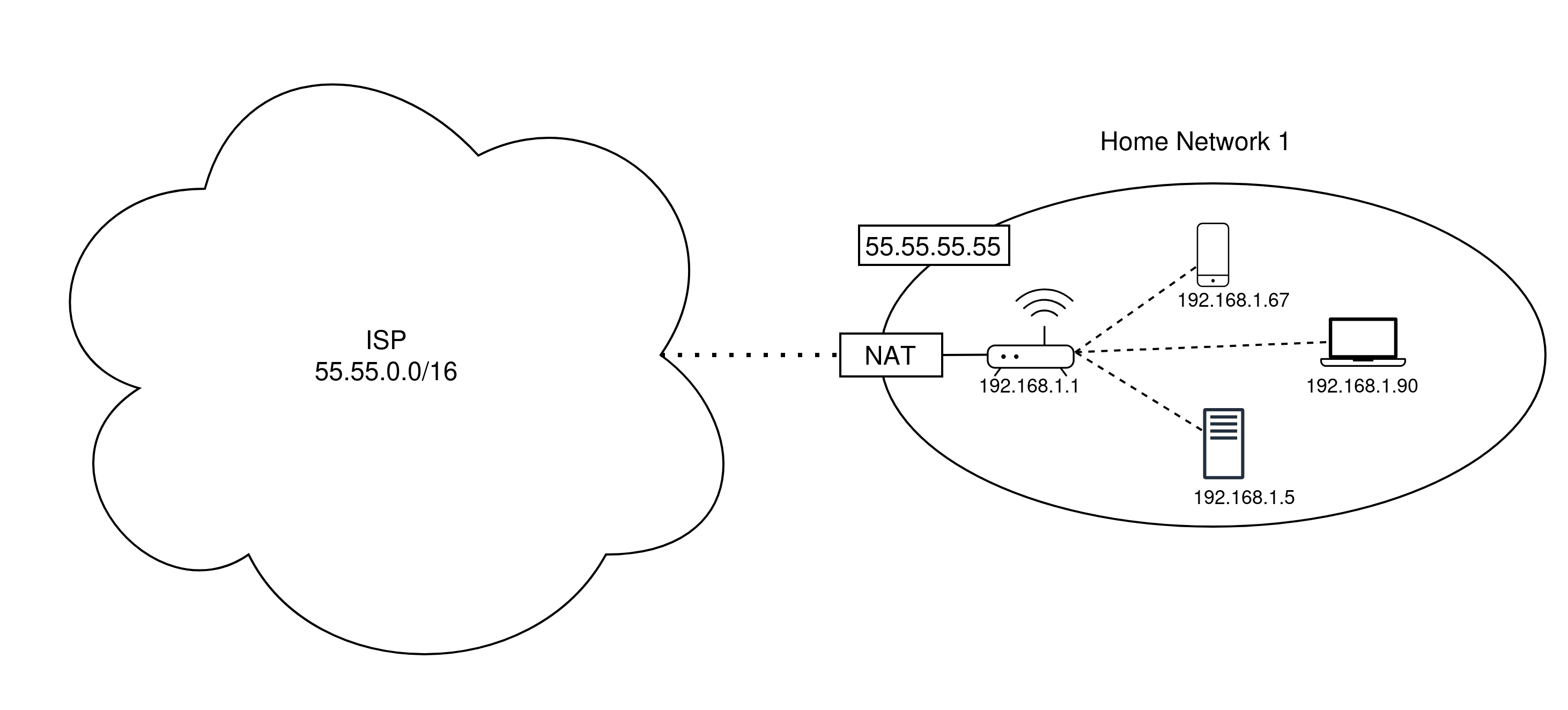

In 1994, the Network Working Group proposed Network Address Translation (NAT) as a “short-term” solution to the growing scarcity of IPv4 addresses. [1] Though IPv6 adoption has steadily increased over the past decade [2], NAT with IPv4 addressing, assigned via DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol), has remained the default addressing scheme for local area networks (LANs), from small home networks to massive enterprise intranets. As the name suggests, NAT is the process of translating a dynamically assigned local IP address to a public address. In typical home networks, the public IP address is assigned by the network’s internet service provider (ISP). Private IP addresses occupy specific blocks of spaces, allowing for roughly 17 million private addresses per network.2 See Figures 1 and 2.

The differentiation of public and private addressing

schemes solves the scarcity issue, but complicates

direct communication between hosts across

networks. For example, say a WiFi-connected laptop with

private IP address 192.168.1.5 attempts to

establish a secure connection to some external website

with public IP address 5.5.5.5 and

constructs the following packet:3

SRC IP SRC PORT DEST IP DEST PORT DATA

192.168.1.5 5555 22.22.22.22 8080 CLIENT HELLOThe packet first arrives at the home router or

gateway, which determines the destination IP is outside

of the network. The router naively forwards the packet

to the next hop, eventually arriving at the destination.

The problem arises when the server at

22.22.22.22 reads the SRC IP

field and is unable to respond, since the address is

private and not reachable. This is known as the

problem of NAT traversal.

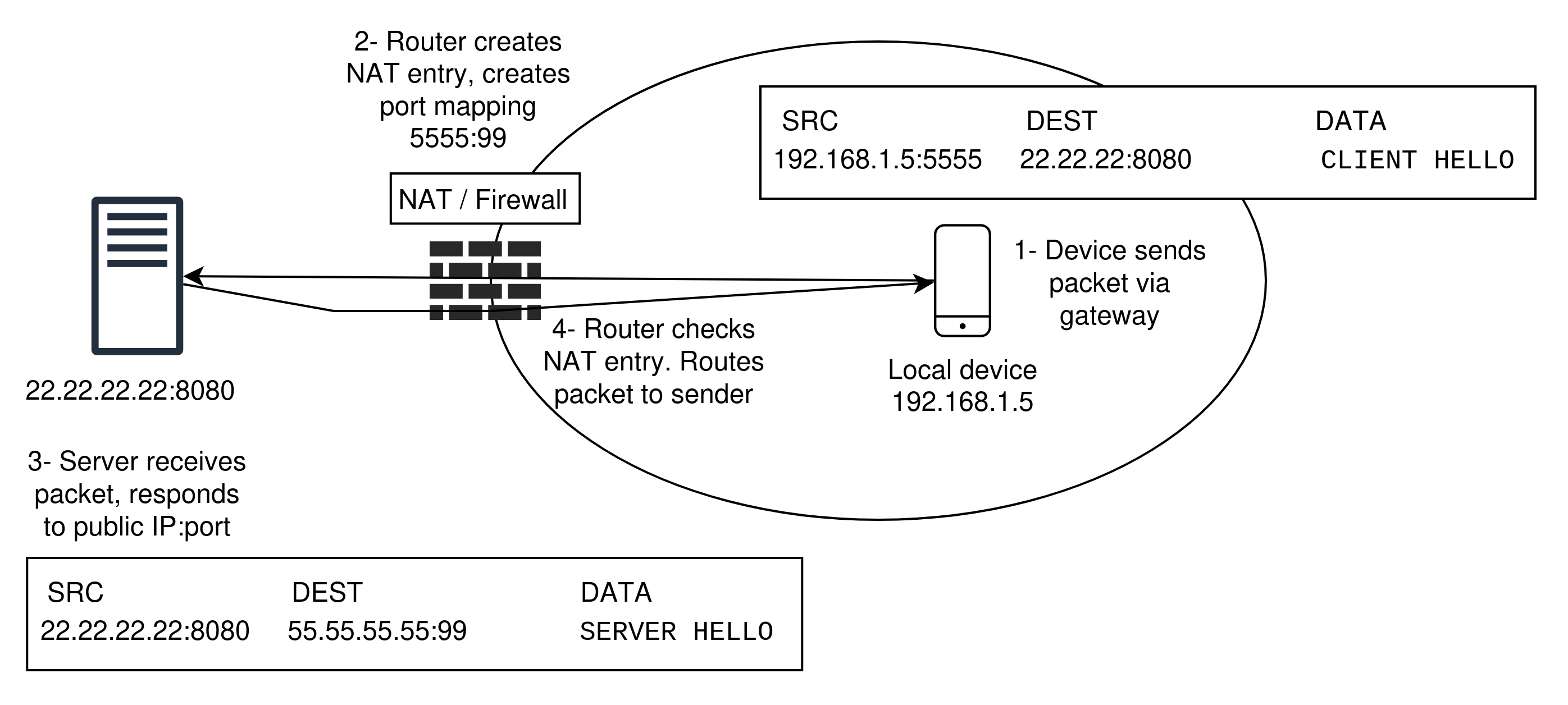

Gateways solve this issue by establishing NAT tables, that contain dynamic records of active connections between end devices. The NAT table for the above packet would result in the following record:

| Internal IP | Internal Port | External IP | External Port | Destination IP | Destination Port |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 192.168.1.5 | 5555 | 55.55.55.55 | 99 | 22.22.22.22 | 8080 |

The gateway device will map each outgoing connection

to an external port, and replace the SRC IP

on the initial packet with the public IP address of the

network (in this case 55.55.55.55) and

SRC PORT with the newly allocated external

port (99). The end server at

22.22.22.22 receives the following packet

containing the client’s public address:

SRC IP SRC PORT DEST IP DEST PORT DATA

55.55.55.55 99 22.22.22.22 8080 CLIENT HELLOThe server can successfully respond:

SRC IP SRC PORT DEST IP DEST PORT DATA

22.22.22.22 8080 55.55.55.55 99 SERVER HELLOThe gateway device receives the above packet and is

able to determine the destination based off of the

destination port and forwards the message to the client

at private address 192.168.1.5. Not only do

NAT tables solve the problem of traversal, but

consequently serve as a network firewall by

preventing unauthorized incoming traffic. Without a

valid entry in the NAT table, packets will be dropped.

See Figure 3.

It should be

noted that there are four main variations in types of

NAT enforcement, which each provide their own level of

security. We describe them below:

It should be

noted that there are four main variations in types of

NAT enforcement, which each provide their own level of

security. We describe them below:

Full Cone NAT: Allows any incoming packet directed to a public port once the NAT entry is created for that port. For example, once the gateway forwards the first outgoing packet to the website at

22.22.22.22, any packet from any IP address can then reach the client host at192.168.1.5. Though the most simple implementation, it is generally considered insecure and is not widely used on home routers.Address-Restricted NAT: Also known as Restricted Cone NAT, this variation allows incoming traffic to a host only if the source IP of the incoming packet matches the entry in the NAT table with the same destination IP, regardless of port number. In the above example a packet sent from address

22.22.22.22with any port directed to55.55.55.55:99will be accepted.Port-restricted NAT: This is similar to Address Restricted NAT, but the source IP and port addresses of an incoming packet must be present in the NAT table. For example, a packet from

22.22.22.22:8080will be accepted since the destination port matches for this connection, but22.22.22.22:8081will be dropped.Symmetric NAT: The most restrictive variation. For every outgoing connection, a separate port mapping is made for each destination. Incoming packets must match exactly the destination port and IP address for that record. For example, if the same client initiates a new connection to another external host at

6.6.6.6:80the resulting NAT table would be updated:

| Internal IP | Internal Port | External IP | External Port | Destination IP | Destination Port |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 192.168.1.5 | 1234 | 55.55.55.55 | 99 | 22.22.22.22 | 8080 |

| 192.168.1.5 | 1234 | 55.55.55.55 | 4445 | 6.6.6.6 | 80 |

An incoming packet from 6.6.6.6 must

specify the exact destination port of 4445.

Otherwise, the packet will be dropped. This differs from

Port-restricted NAT, where a single record and port is

created for all outgoing connections from the client. By

enumerating the NAT enforcement variations, we can see

they offer a wide range of security. Full Cone NAT

essentially opens up the internal device to any incoming

packet once a single outgoing request is made, whereas

Symmetric NAT ensures each incoming packet must

originate from a previously connected host.

As security increases, so do the obstacles for non-standard connection types. For standard client-server interactions, where a device on a local network initiates a connection with an external host (e.g., web browsing), any NAT technique works without complications. However, non-standard connection types face significant hurdles. Peer-to-peer (P2P) connections (e.g., gaming, video calls, torrenting) must overcome the restrictions imposed by the stricter enforcement techniques, often at the expense of connection speed or reliability. For example, WebRTC — a popular framework for P2P communications — will not work as expected with Symmetric NAT. Instead, clients must utilize proxy TURN servers (Traversal Using Relays around NAT), which act as intermediaries between peers. Though this technique allows for data transfer, it increases latency as the connection is no longer direct.4 For other non-standard connection types, sometimes NAT traversal is simply impossible unless new mechanisms are introduced.

Because NAT tables always first require an initial outgoing connection, devices that may never initiate connections will not attain a port/address mapping from the gateway device. Internet-of-things (IOT) devices, which commonly live behind home network firewalls, fall under this category, as do home media servers. For this reason, developers have proposed and implemented new frameworks and protocols that allow for NAT traversal. The rest of this work is dedicated to explaining these mechanisms, along with the layers of security they have. We begin with a popular approach: UPnP (Universal Plug and Play).

3. UPnP: Automating NAT Traversal

UPnP is a set of protocols that allow for devices within a network to communicate with each other and the outside world, discover and advertise services, and issue controls all with zero configuration. UPnP was designed for ease of use alongside the growing amount of internet-enabled “smart” technologies. Within the UPnP framework service devices, also called control devices, are hosts that offer some kind of service, where control points are clients that can consume, control, and subscribe to these services. For example, a “smart” thermostat is a service device that can be controlled by a laptop (control point). There are three layers of UPnP interactions that define how devices are configured and controlled:

- Discovery & Advertisement: In this

phase, service devices advertise their services using

Simple Service Discovery Protocols (SSDP), periodically

sending multicast

SSDP NOTIFYmessages to a fixed address and port.5 Control points can discover new services through issuing aSSDP M-SEARCHrequest. Both discovery and advertisement uses SSDP over HTTPU (HTTP over UDP). - Description: Service devices respond to discovery by supplying a URL to a XML file. Once a control point has this URL it requests the XML file with HTTP. The response is the device description document that outlines the actions available to the control point.

- Control & Eventing: Control points dispatch actions directed to the control URL of service devices using SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol) over HTTP. Control points also subscribe to state changes of the service device by passing a callback URL where the service can publish events.

Under regular circumstances, these three layers allow

for clients to easily discover and control

network-attached devices. Furthermore, UPnP also enables

devices to bypass NAT with ease. A UPnP-enabled router

accepts an AddPortMapping control, which

removes restrictions on incoming traffic to the specific

port. Moreover, it is possible to forward traffic

directed to the specific port to an address

outside of the local network. Self-hosted media

server software often utilizes UPnP’s automatic port

mapping control to accept and respond to incoming

traffic, allowing for remote access to resources.6 Though UPnP removes

barriers to NAT traversal and allows for zero

configuration of IoT devices, it is generally considered

insecure [3].

3.1 UPnP Vulnerabilities

Several reports [3, 4, 5] have illustrated the significant weaknesses of UPnP networks. Most exploits take advantage of the fact that UPnP has no built in authentication or verification mechanism. We now categorize a non-exhaustive list of attacks against UPnP. This list builds on the one established in [3], appending the attacks described in [4, 5].

3.1.1 Discovery

A Denial of Service via discovery message flooding is trivial. In this attack a malicious control point can flood the network with discovery requests. This is a serious problem for devices such as an IoT-enabled pacemaker, which would become overloaded with discovery requests that prevent normal functionality [3]. Furthermore, as UPnP discovery uses HTTPU, UDP packets are vulnerable to source address spoofing. In this attack, an attacker can forge the source address of a discovery packet, which directs responses to a victim’s devices. With multiple malicious machines performing this spoofing, this lays the foundation of a Distributed Denial of Service Attack (DDoS).

3.1.2 Advertisement

A malicious device can pose as a valid service device

and perform service advertisement by simply issuing

multi-casted SSDP NOTIFY messages. A victim

cannot distinguish between a valid and invalid service

and could be directed to a forged LOCATION

URL of the malicious description document. Similar to

discovery, UPnP-enabled networks have no protections

against advertisement message flooding [3].

3.1.3 Eventing

A malicious control point can overwhelm a service device with event subscription messages, preventing other control points from receiving updates from the service. Likewise, an attacker can easily spoof the callback URL in the event subscription message to direct to a victim’s machine. If amplified, this vulnerability is leveraged for an effective DDoS attack [3].

3.1.4 Control

Vulnerabilities in the UPnP control mechanism are

perhaps most relevant to our discussion on NAT traversal

and securing self-hosted servers within private

networks. Enforcing access control and authentication

using the DeviceProtection service is

optional [6], and the majority of devices do

not implement it. Due to this deficiency, the attack

surface of UPnP control endpoints is significant. For

brevity, we limit the discussion of these attacks to

those related to port forwarding.

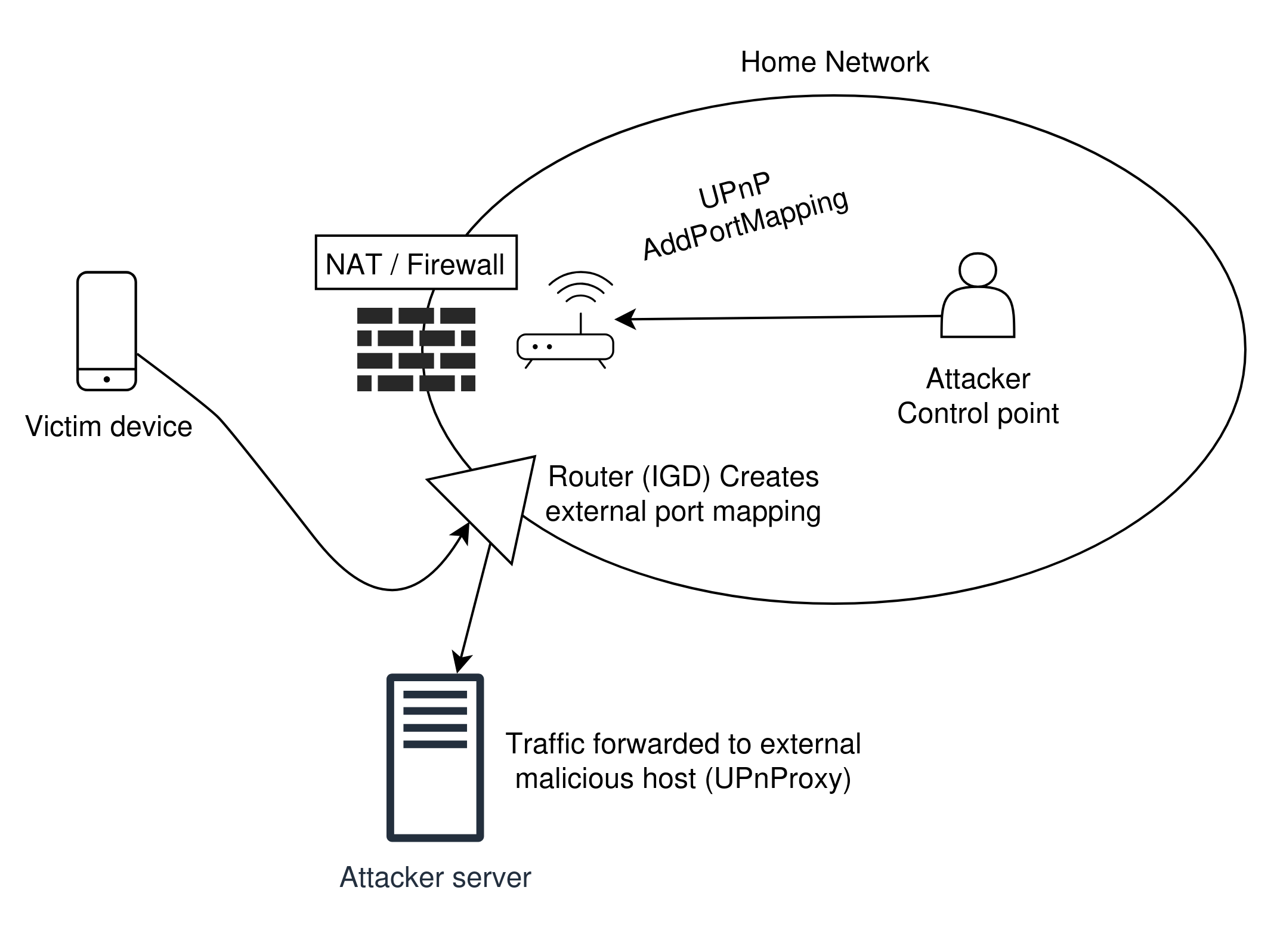

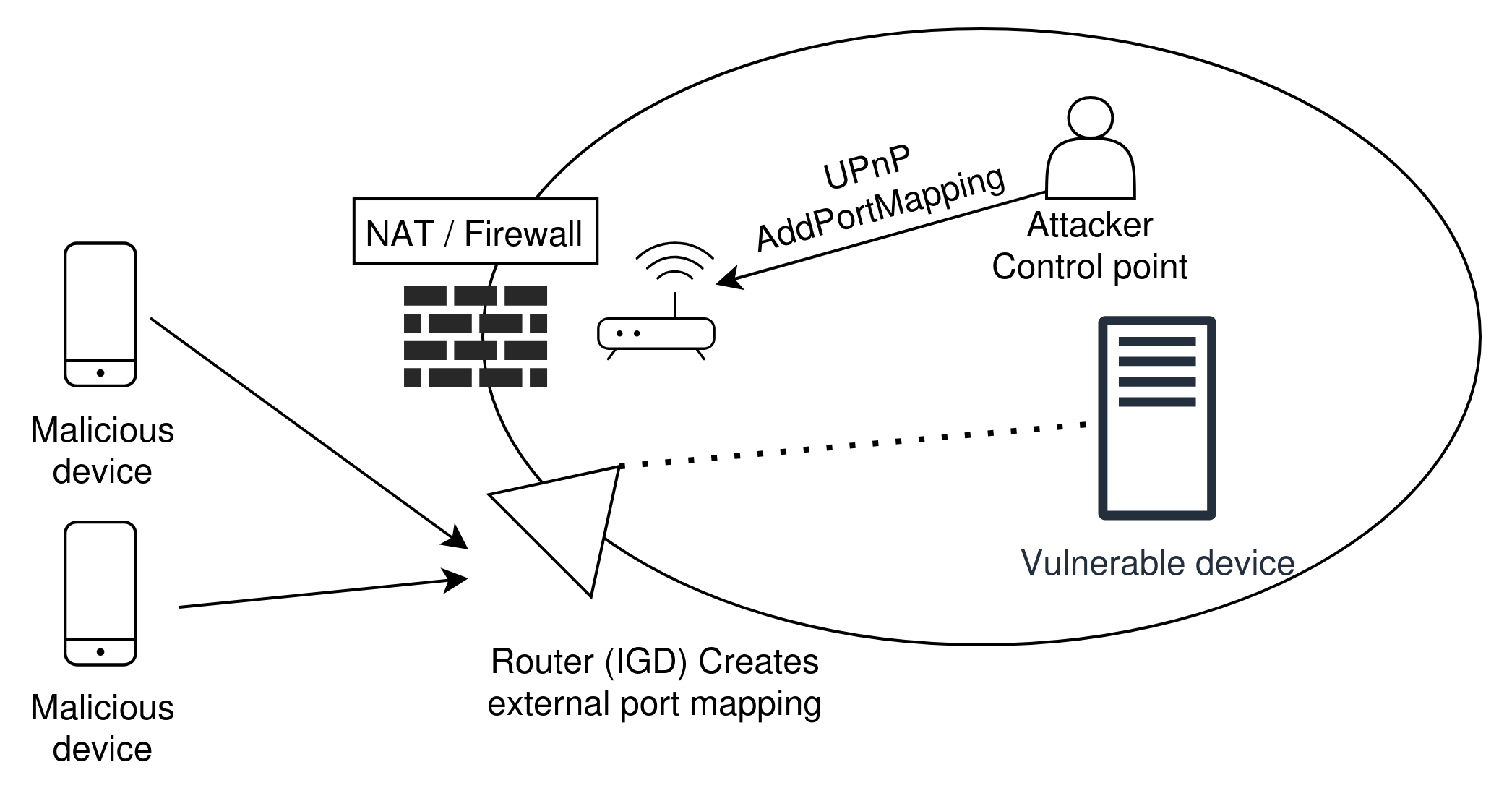

UPnP-enabled routers, also called Internet Gateway

Devices (IGD) allow control devices to issue

AddPortMapping commands, which effectively

bypass NAT restrictions to allow external traffic to any

device on the network. Attackers can easily leverage

this feature to create back doors, compromise entire

networks, and route traffic at will. One such attack [3,

5] is UPnProxy, which was launched in 2018 and

impacted close to 300,000 routers at the time. In this

attack, a malicious control point sends an

AddPortMapping command to the vulnerable

router, specifying an arbitrary URL as the forwarding

address. Incoming traffic to the network at the port

will be redirected to the malicious URL. Not only is

this an effective mechanism to spread viruses, but could

also be utilized for a DDoS attack if the forwarding URL

is set to a victim’s IP address.

Another variant of UPnProxy sets the forwarding address to a victim’s device within the private network, thereby allowing all traffic to reach the device via the exposed port. In 2018, the UPnProxy attack vector was utilized in the EternalSilence campaign, which compromised roughly 277,000 routers.[5] The attack opened up ports 139 and 445 on vulnerable routers, allowing attackers to deliver two previously known exploits, EternalBlue and EternalRed. EternalBlue, an exploit developed by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), leveraged a weakness in the SMB (Server Message Block) protocol (which runs on ports 139 and 445) to allow for remote code execution via a buffer overflow vulnerability. The 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack propagated via machines compromised by EternalBlue. EternalRed targeted Samba, the Linux/Unix implementation of SMB, and leveraged a weakness in the shared library loading mechanism that allowed for remote code execution. Though both these exploits were previously known and patched, EternalSilence exposed machines that were still vulnerable to both attacks, but had previously been protected behind network firewalls.[7]

3.2 Mitigation and solutions

By analyzing the extensive attack surface of UPnP, we can conclude that the protocol should be considered insecure. Though some devices and networks implement access control mechanisms and frequently update firmware, since there is a lack of standardized security practice in IoT development, there will always be a large attack surface since many devices either are not updated to recent firmware and control mechanisms are not protected by authentication.

The authors of [3] have proposed an authentication mechanism, whereby service devices register their specification documents through a Certificate Authority (CA), which in turn issues a signature that prevents device impersonation. Control devices register with a Registration Authority (RA) before joining the network, which issues CapTokens (Capabilities Tokens), allowing for fine-grained access control. Every action must be coupled with a CapToken, which is verified by the RA.

This is a robust and straightforward solution that adds authentication and authorization layers by default to the UPnP scheme. However, the approach would break backwards compatibility and has yet to be implemented.

Now that we have presented a thorough overview of UPnP and its pitfalls, we can recommend that admins of self-hosted servers disable it entirely. As self-hosted media servers do not require or allow for specific control actions, the use of UPnP as a method of remote access is overkill. We now present the next option for remote access, which is preferable to UPnP, but still vulnerable to attacks.

4. Port forwarding

The simplest solution for remote access to self-hosted resources is to configure manual port forwarding and disable UPnP entirely. This approach bypasses the implicit firewall established by a NAT table by imposing an explicit firewall rule and port mapping in the router. While this rule could specify allowed IP addresses, this is typically too limiting since remote devices likely do not have static IP addresses. Mobile networks update IP address assignment very frequently. Likewise, the public IP assigned to home networks is rarely static. The latter is an issue we will discuss in depth later on. Because of this, port forwarding generally allows all traffic from the internet to a specified port.

While simple, manual port forwarding has serious security implications, as the forwarded port inherits any of the vulnerabilities present on the self-hosted server. The next section surveys real CVEs on two popular media servers. In doing so, we attempt to clarify the threat model against these services.

5. Threat model of home media servers

In this section we conduct a survey of active CVEs and past exploits in two popular media server applications to make clear the security risks of self-hosting.

5.1 Plex

Plex Media Server (PMS), a proprietary software, is perhaps the most popular option for media servers and offers third-party authentication, support for multiple accounts and users, and many clients (Linux, iOS, Android). Although Plex offers decent security, with MFA support and suspicious login activity notification, several significant vulnerabilities have been discovered.

In August 2025, Plex Inc. announced that a vulnerability (CVE-2025-34158) had been disclosed through their Bug Bounty Platform with the highest possible CVSS score of 10.0, later downgraded to an 8.5. Though the details of the vulnerability have yet to be released, at the time of the announcement, an estimated 428,083 devices were susceptible to the attack. Plex sent an urgent email to users urging updates to the patched version of PMS.[8]

In 2023, attackers leveraged a Plex Media Server vulnerability, leading to a massive breach at LastPass, a popular password manager service. Attackers gained access to home IP addresses of LastPass employees who held master encryption keys. A network scan revealed a Senior DevOps engineer was self-hosting an outdated version of Plex Media Server, which contained a remote code execution vulnerability (CVE-2020-5741). Attackers exploited this weakness to install a keylogger on the engineer’s home system. The keylogger eventually captured the secret credentials to the employee’s account, which granted attackers access to customer data, database backups, and source code. [9]

5.2 Jellyfin

Jellyfin is an open-source, volunteer-maintained media server software, which has an active community of users and developers. As opposed to Plex, Jellyfin has no third-party authentication mechanism. All services in Jellyfin are run on the host system. There have been fewer widespread attacks on Jellyfin compared to Plex, but researchers have still discovered serious vulnerabilities.

CVE-2023-30626

Prior to the patched Jellyfin version 10.8.10, this

exploit allows a low-privileged user to perform remote

code execution on Jellyfin instances due to improper

input sanitation in the

POST /ClientLog/Document endpoint, which is

used to create a valid log file. An attacker can target

the endpoint by supplying an arbitrary path (e.g.,

../../Plugins) and malicious

.log file. The log file is executed via a

separate stored XSS attack (CVE-2023-30627), whereby an

admin action unknowingly sets the ffmpeg

encoder path to the previously uploaded

.log file. Upon server reboot, Jellyfin

validates the encoder path by running it, which thereby

executes the malicious payload.

CVE-2025-31499

A previous vulnerability (CVE-2023-49096) exploits

improper input sanitation in unauthenticated video

streaming endpoints to allow for argument injection in

ffmpeg codec parameters. Once an attacker

has a valid videoId it is possible to pass

arbitrary values. For example, an attacker could pass a

codec parameter -i that includes a path to

a malicious URL disguised as a DLL (Dynamic Link

Library) plugin. The patch for CVE-2023-49096 involved

input sanitation on the exposed endpoints, but certain

parameters remained unsanitized and therefore the

previous patch can be bypassed.

5.3 Summary

Though the list of above vulnerabilities is non-exhaustive, we hope to make clear the types of threats and vulnerabilities of self-hosted software such as Jellyfin and Plex. The following sections will describe how an administrator can mitigate the risk of attack apart from simple software updates, as zero-day exploits always remain a real possibility.

6. Local only

The simplest way to address the challenges imposed by NAT enforcement, as well as vulnerabilities in media servers, which we described in the previous section, is to disallow any outside traffic from reaching the service in question. From the administrator’s side, this simply involves disabling any port forwarding as well as UPnP. As we will discuss in the next section, Plex includes a relay service which allows for remote access without port forwarding. For a true local only approach, this option should be explicitly disabled as well. Preventing all incoming traffic to the locally hosted server instance significantly lowers the risk of attack. This is sensible, as any software an administrator runs on the server will inevitably contain vulnerabilities. This incurs a significant tradeoff, however. Remote access to resources (e.g., streaming audio on mobile devices) is not possible. Though most desktop and mobile media client software typically permits downloads, this is inconvenient if a user does not have sufficient storage or simply wishes to access an item that has not been previously downloaded.

We now explore two solutions to the remote access issue, namely Port Forwarding Services (PFS) and Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). We explain that both drastically improve on the weaknesses of UPnP and manual port forwarding. We show, however, that the former still contains vulnerabilities while the latter impacts convenience.

7. Port Forwarding Services (PFS) and Relays

Port Forwarding Services (PFS) avoid the complexities of NAT by providing a bridge between clients external to a network and end devices within the network. These services are typically offered by third-party providers and involve little to no configuration. Popular PFS providers include Ngrok, Oray, Portmap.io, among several others.

In the PFS approach, the local machine maintains a

persistent outgoing connection to the PFS server,

thereby establishing a NAT entry. Incoming requests are

routed to the address of the PFS server, which then

forwards traffic through a tunnel to the end device,

effectively bypassing NAT restrictions. PFS can be quite

useful to bypass network firewalls with ease. For

example, a software developer utilizing Ngrok can work

on a website running on a local device at

192.168.1.5:3000. Clients outside of the

network can interact with some public URL (e.g.,

https://foo.ngrok.io) that establishes

communication to the locally hosted website.

The authors of [10] have conducted a comprehensive security review of PFSes, with a focus on Ngrok and Oray – two of the most popular services. Their findings indicate that a large percentage (18.57%) of these services have no enforcement mechanism for access control or authentication. The authors also discovered that the vast majority (76%) of PFS IPs are likely malicious. Among vulnerabilities including possible Man-in-the-Middle attacks (MITM) through weak encryption schemes, the authors indicate that weaknesses in PFSes are generally due to user misconfiguration, where organizations frequently utilize PFSes without the intention of making resources publicly accessible. Though PFSes can help solve the problem of dynamic DNS, they do not enhance security of self-hosted media servers over standard manual port forwarding, other than masking the public IP address of the server.

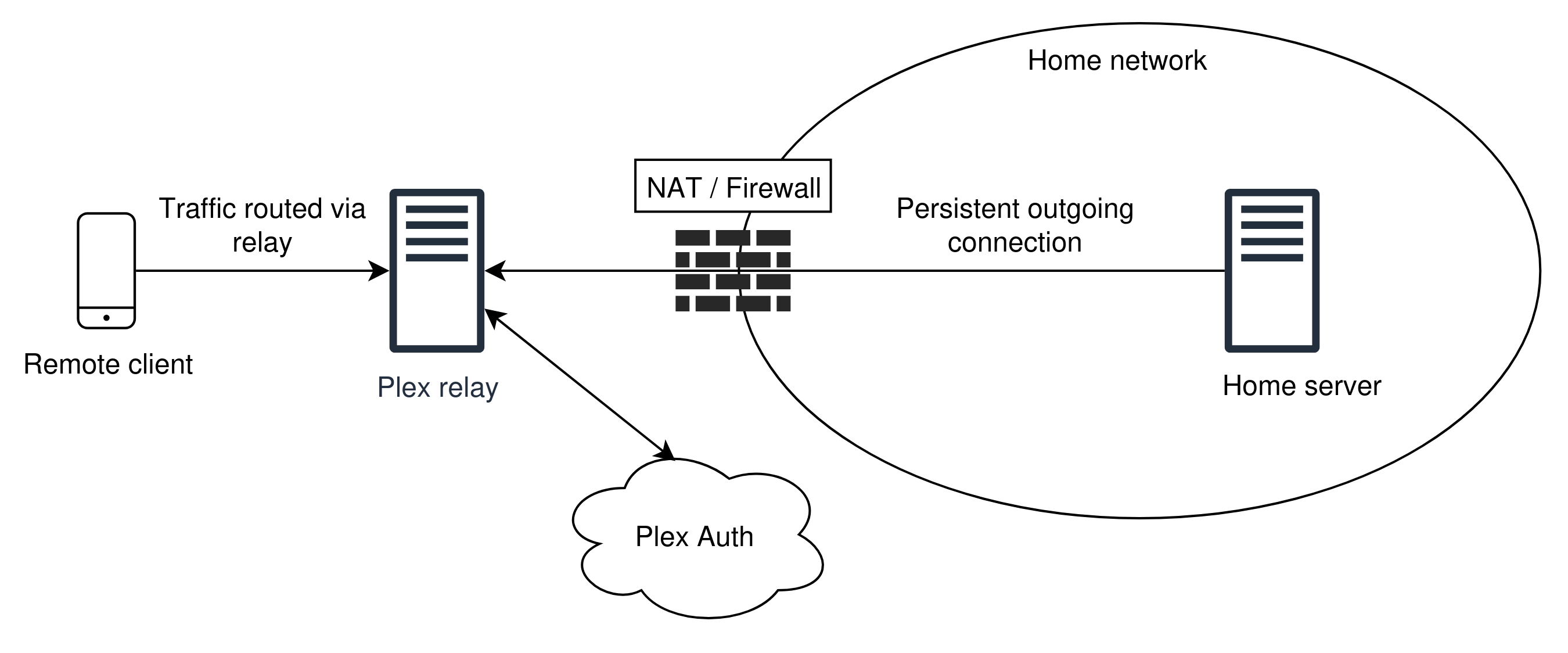

7.1 Plex Relay

Plex offers a service called Plex Relay, which simplifies remote access by routing traffic from remote clients through a relay service that Plex maintains. Plex Relay is classified as a specialized port forwarding service that is application-specific. Other PFS providers allow service-agnostic port forwarding. Plex Relay, however, is privately maintained. Similar to other PFSes, Plex Relay bypasses NAT restrictions as the Plex-enabled server maintains a connection with the relay point. Plex enforces proper authentication and only establishes the tunnel if an authenticated user has proper credentials. For this reason, Plex Relay is considered a secure option for remote access provided that the intermediary service is not compromised. Unfortunately, Plex limits bandwidth through the relay to 2 Mbps. This makes the relay service unsuitable for higher quality streaming or for multiple simultaneous connections. Furthermore, as of November 2025, the use of Plex Relay is only permitted for Plex paid accounts.

8. Virtual Private Networks (VPNs)

This section proposes the use of self-hosted VPNs alongside a VPS-hosted reverse proxy as an ideal method for securing home media servers. We first briefly address two more challenges to remote access. We then argue why VPNs and reverse proxies solve both of these problems, as well as NAT restrictions and security concerns:

8.1 Dynamic IP Addressing

Thus far, the solutions for remote access to self-hosted resources either leave the network vulnerable to attacks (UPnP, Manual Port Forwarding, PFS) or are overly restrictive (Plex Relay). We have yet to discuss other barriers other than NAT traversal. One important issue relates to dynamic IP addressing. In typical home networks, the public IP address is assigned by an ISP and can change at any point. This is a problem for remote access, since clients must know the correct location of the home server.

There exist Dynamic DNS providers (like Duck DNS, DynDNS), that allow users to configure a hostname that will point to the current public IP of a home network. A service runs on a device within the home network that periodically updates the DNS record with the DDNS provider. Plex offers a similar service that is automatically configured once you connect a Plex Media Server with a Plex account.

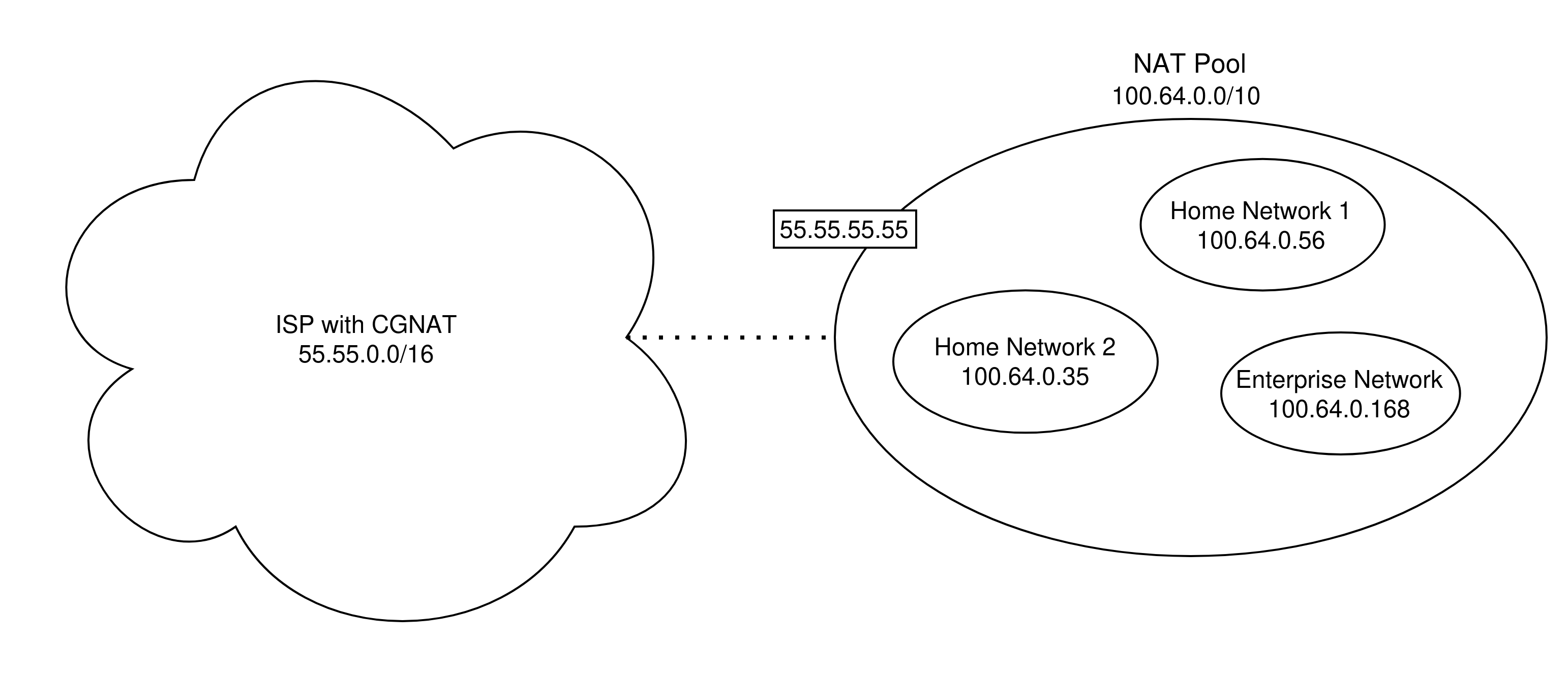

8.2 CGNAT

CGNAT (Carrier-Grade NAT) is another mechanism to address the scarcity of IPv4 addresses. Under CGNAT, ISPs group multiple home networks under one single sub network. Each single home network is thus granted its own private IP address. Self-hosted media servers on CGNAT cannot use standard port forwarding approaches, as standard NAT traversal techniques do not work at all.

8.3 VPNs: Secure Solutions for Remote Access

A Virtual Private Network (VPN) is a mechanism for establishing encrypted communication channels (i.e., tunnels), thereby hiding the data in transit and information about the sender and receiver of that data. There are several classifications of VPNs, each with distinct use cases. For our purposes, this section discusses remote access VPNs (e.g., client-to-site), which allow devices to securely connect to a remote network. We begin by exploring several different remote access VPN architectures, discussing how each addresses the problem of NAT traversal. We conclude by proposing a recommended architecture for VPNs in tandem with self-hosted media servers on home networks.

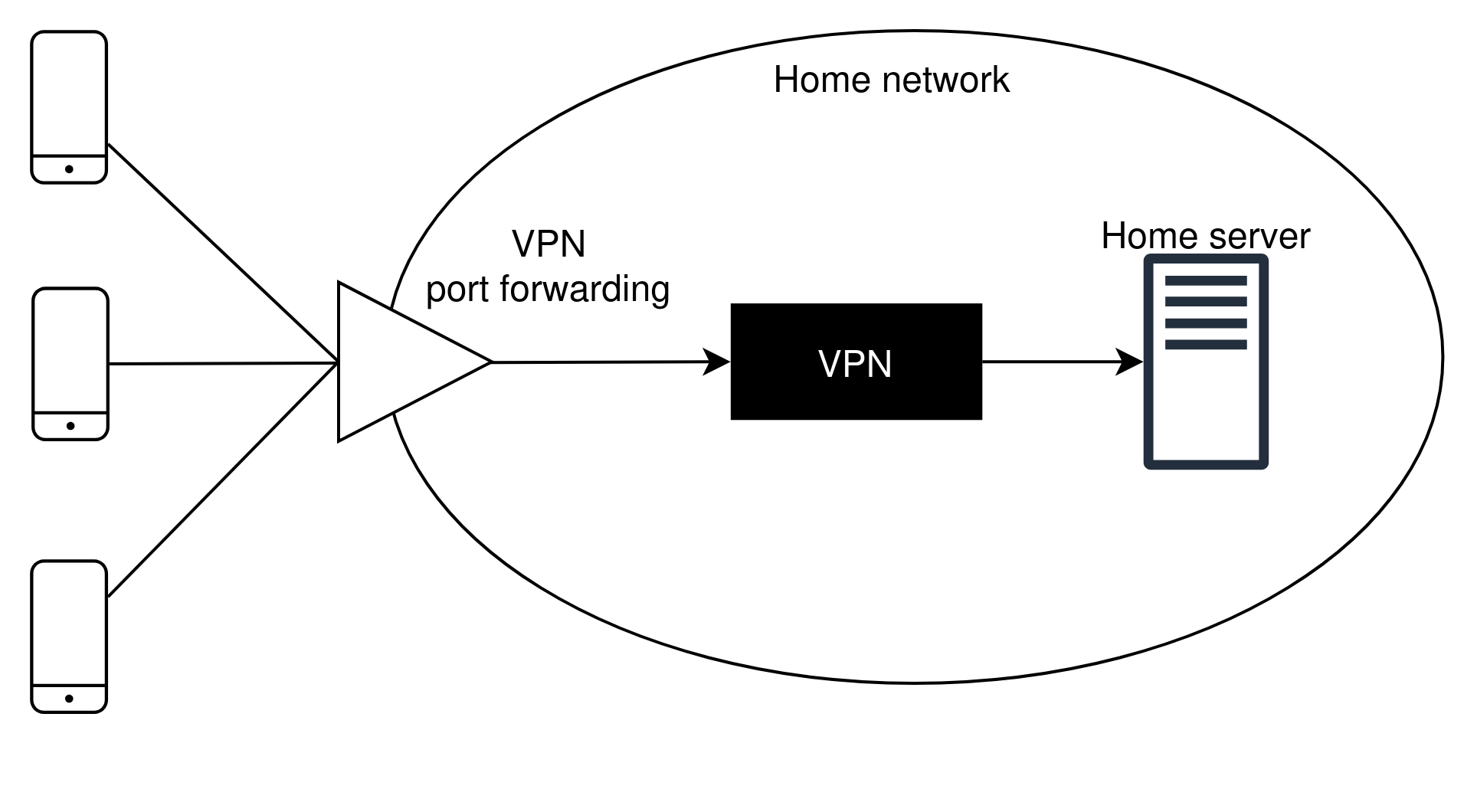

8.3.1 Traditional client-to-site VPNs

In this approach a VPN gateway server listens for connections from clients. Once a connection is established between the client and server via key exchange, the client encrypts network packets using a shared session key and sends TCP or UDP to the server. The server decrypts the packets and can respond with the same mechanism. The gateway offers the client access to other devices within the network.

Within a typical home network, a media server can also act as a VPN gateway. For this approach to work, port forwarding must be enabled on the router to allow incoming traffic to bypass NAT restrictions. Provided the underlying encryption schemes are secure, it is infeasible for an attacker to attempt to break through a VPN gateway. If a network is behind CGNAT, this approach will not work for reasons we have already discussed. Therefore, an intermediary gateway VPN must be hosted on a Virtual Private Server (VPS), where the home device establishes a persistent outbound connection to the external host.

Two common VPN servers are OpenVPN and WireGuard. OpenVPN is more robust, supports a wide range of encryption schemes, uses TLS key exchange, and provides fine-grained configuration. WireGuard is a newer and more performant option, with less control over underlying encryption mechanisms.

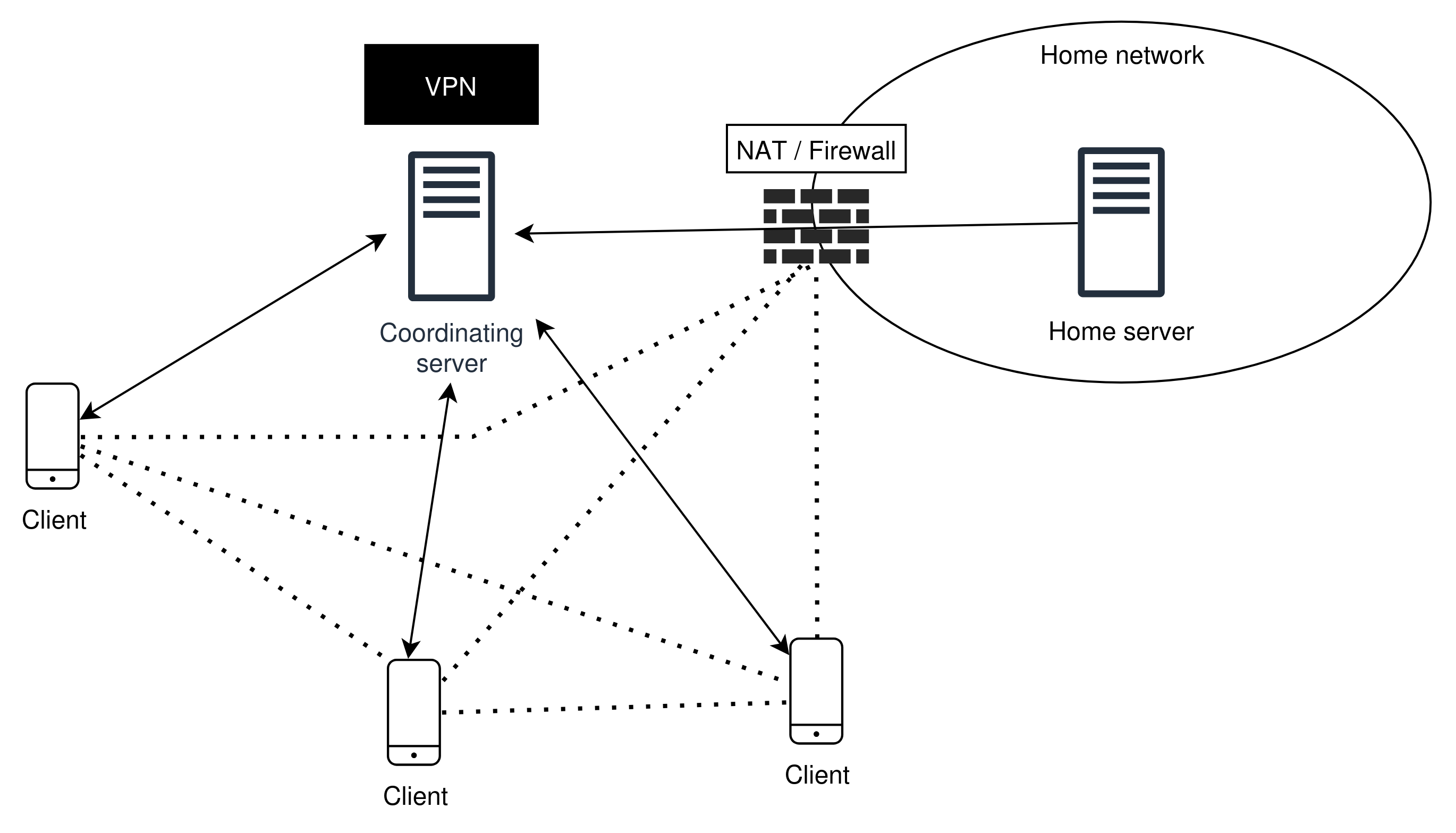

8.3.2 Mesh VPNs

Instead of the traditional client-server approach, Mesh VPNs allow peer-to-peer (P2P) communication between clients across networks (home, enterprise, 5G, etc.). Under this approach, all connected devices behave as if on the same private network. To facilitate communication, a coordinating server receives connection requests from clients. To establish an encrypted tunnel between two clients, the coordinating server provides the respective IP addresses and ports to which an outgoing P2P connection should be made. Each client performs UDP hole punching, simultaneously emitting UDP packets directed to the other peer’s address. This creates a NAT entry, allowing for ongoing P2P connection. If both clients have routers that enforce symmetric NAT, however, connection will fail since each outgoing connection contains a separate external port mapping. This results in each peer directing packets to an incorrect port. In this case, mesh VPNs typically utilize TURN servers as fallbacks. This is similar to WebRTC’s approach, as we discussed earlier.

Mesh VPNs can successfully bypass CGNAT, provided the coordinating server is publicly accessible. Mesh VPNs can be configured to work like typical client-to-site VPNs by designating a peer as a gateway or exit node, routing other peer’s requests to some other destination (like a media server API).

8.3.3 Recommendations

As VPNs only allow authorized traffic to reach the protected network, the vulnerabilities of self-hosted software cannot be effectively exploited by attackers unless VPN security is compromised. For this reason, VPNs are the most secure approach for remote access. For self-hosters who prioritize convenience, we recommend the use of third-party mesh VPN providers like Tailscale or ZeroTier. For self-hosting purists who wish to avoid reliance on cloud providers, a local WireGuard instance is a practical option. Assuming the network is not under CGNAT, setup involves downloading and configuring the VPN server and adding a single port forwarding rule enabled on the router. Both of these approaches offer the same level of security, from a cryptographic perspective.

It should be noted that the use of client-to-site VPNs requires each remote device configure a compatible VPN client. This technical overhead can be cumbersome. As the authors of [11] indicate, the administrator should consider barriers like power consumption for mobile devices, as well as the implications of “exporting” all home devices to remote clients. Without additional network configurations like a DMZ, all devices within a private network are accessible to the remote clients. The local VPN approach is sensible when the size of the connected parties is low and each member is inherently trusted by the administrator.

9. Conclusion

This work has examined the threat model against locally hosted media servers and proposed secure solutions for remote access to home networks. A thorough review of NAT has demonstrated the importance of secure mechanisms to allow for NAT traversal. We have demonstrated that although UPnP enables zero-configuration of IoT devices, including remote access to self-hosted media, the protocol stack contains significant attack surfaces, which have allowed for large-scale attacks like EternalSilence. Though manual port forwarding avoids many of the weaknesses baked into UPnP, we also acknowledged that media server software will always be at risk for zero-day exploits and unpatched vulnerabilities. After discussing the limits of PFSes and relays, we propose self-hosted VPN architecture as the most secure option for remote access. Though configuration is more involved than previous approaches, VPNs add a robust and community-tested authentication layer, effectively protecting home networks and resources.

Though local instances of VPNs afford an ideal level of security, the technical overhead is a barrier for many who do not have the time or background to configure and maintain these architectures. Third-party Mesh VPNs are ideal for low-cost and simple configuration, but this approach relies on cloud providers. For some, this may go against the self-hosting ethos entirely. Future work should therefore explore software and hardware projects that enhance the security of fully self-hosted architecture to maximize ease of use.

*This blog post was originally a research paper I wrote for a network security class at NYU Courant.

References

[1] K. Egevang and P. Francis, “The IP Network Address Translator (NAT),” RFC 1631, Internet Engineering Task Force, May 1994.

[2] Google, “IPv6 Statistics,” Google IPv6. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/intl/en/ipv6/statistics.html

[3] M. A. Hakim, H. Aksu, A. S. Uluagac, and K. Akkaya, “An Overview of UPnP-based IoT Security: Threats, Vulnerabilities, and Prospective Solutions,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.02587, Nov. 2020.

[4] U. Garg, P. Mishra, N. Gupta et al., “IoT botnets unveiled: Architectural analysis, threat vectors, and cutting-edge detection techniques,” Cluster Computing, vol. 28, art. 945, 2025, doi: 10.1007/s10586-025-05633-1.

[5] S. Monette, D. Johnson, P. Lutz, and B. Yuan, “UPnP Port Manipulation as a Covert Channel,” in Proc. The World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering and Applied Computing (WorldComp), Athens, Greece, 2012.

[6] UPnP Forum, “DeviceProtection:1 Service for UPnP Version 1.0,” Standardized DCP (SDCP), Version 1.0, Feb. 24, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://upnp.org/specs/gw/UPnP-gw-DeviceProtection-V1-Service.pdf

[7] C. Seaman, “UPnProxy: EternalSilence,” Akamai Security Intelligence and Threat Research Blog, Nov. 7, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.akamai.com/blog/security/upnproxy-eternal-silence

[8] “Plex Media Server vulnerability exploited in attacks (CVE-2025-34158),” Help Net Security, Aug. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.helpnetsecurity.com/2025/08/27/plex-media-server-cve-2025-34158-attack/

[9] “5 lessons everyone can learn from the LastPass hack,” Proton Blog, Sep. 6, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://proton.me/blog/lessons-from-lastpass

[10] H. Wang, Y. Xue, X. Feng, C. Zhou, and X. Mi, “Port Forwarding Services Are Forwarding Security Risks,” in 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023, pp. 3234-3251, doi: 10.1109/SP46215.2023.10179456.

[11] P. Belimpasakis and V. Stirbu, “A survey of techniques for remote access to home networks and resources,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 1899–1939, Jun. 2014, doi: 10.1007/s11042-012-1221-y.